Dada: 100 Years Later

A century ago, a small group of provocateurs took the stage at Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, starting a movement—now celebrated in a series of exhibitions—that forever changed modern art

By Tony Perrottet

Jan. 19, 2016 12:05 p.m. ET

3 COMMENTS

FOR ART HISTORIANS interested in Dadaism, the impact of the subversive anti-art movement founded in Zurich 100 years ago is illuminated by a simple parlor game: Which artist today has Dada most influenced? Is it Paul McCarthy, whose mischievous ketchup bottles and Barbie dolls recall Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the readymade? Could it be Cindy Sherman, whose classic self-portraits toy with identity in subversive ways? (In 1920, Tristan Tzara invited fellow Dadaists to send him manipulated self-portraits, provoking Max Ernst to re-create himself as “Dadamax.”) Or perhaps Rirkrit Tiravanija, a contemporary artist whose dinner parties turn audience members into an active element of the work? (The rejection of art as a commodity—not to mention the very idea of performance art—can be traced back to Dadaism, says Adrian Sudhalter, curator of Dadaglobe Reconstructed, an exhibition coming to New York’s Museum of Modern Art this summer.) In fact, the better question may be: Which living artist is not influenced by Dada? “The echoes of Dadaism are everywhere,” Sudhalter says. “Dadaism shifted the entire landscape of modernism. It redefined the idea of what art was. It no longer had to be an object you hang on the wall. Art could be an ephemeral performance, a page in a magazine, an object found in the street. The strategies of Dadaism are now part of almost every artist’s vocabulary.”

“The spirit of Dada re-emerges in the puberty of every artistic generation,” explains Adrian Notz, director of Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, where Dada was born. In the 1960s, there was “neo-Dada” practiced by the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Yoko Ono. More recently, “trash art” took the use of found objects to extremes, inspiring artists such as Noah Purifoy and David Hammons. Even more pervasive is Dada’s effect on pop music. “Dada’s most genuine successor was punk rock,” says Notz. The Sex Pistols’ concerts induced the same shock and awe audiences felt a century ago when Dada performances nearly provoked riots. “ David Bowie was a consummate Dadaist, creating his own personas,” Notz adds, a banner of self-invention also carried by Lady Gaga: “She continues the tradition of absurd self-creation. The idea of embracing your inner freak is pure Dada. Don’t put on a mask; develop your personal spirit.”

It may seem odd that Dada’s “primal scream” of anarchy began in Zurich, better known for staid financial efficiency than artistic frenzy. But during World War I, the city flourished as a raucous cultural center whose energy was fueled by refugees from all over Europe. In this atmosphere, Dada was formed by a cosmopolitan coterie of artists who shared a sense of outrage at the savage bloodletting of history’s first mechanized conflict. They were led by the Germans Hugo Ball and his lover Emmy Hennings, the Frenchman Jean Arp, the Swiss Sophie Taeuber and the Romanian Tzara, who would become Dada’s main cheerleader. (In 1916, Zurich was also home to James Joyce, who was writing Ulysses, and Vladimir Lenin, who was plotting political revolution—a convergence that Tom Stoppard celebrated in his play Travesties.) “Zurich is not at all a Dadaist city, but that is exactly why it was born here,” Notz says. “The Swiss qualities of safety and order make it an excellent place for artists to experiment. And Zurich has always been a bubble within Europe. During the Great War, it was described as ‘a birdcage surrounded by roaring lions.’ This very contradiction nourished Dada.”

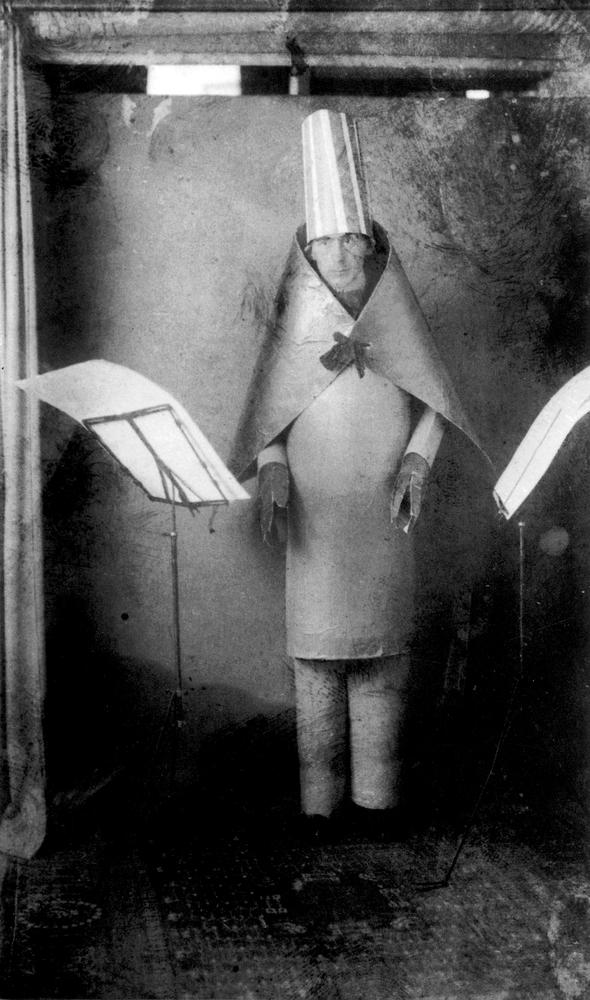

On the night of February 5, 1916, at Cabaret Voltaire, a half dozen wild-eyed young bohemians staged the first Dadaist performance before a bewildered crowd. The walls of the cabaret were decorated with primitivist masks and artworks by the likes of Picasso and Modigliani. Onstage, provocateurs mixed vaudeville acts and expressionist dance with performances that bordered on gibberish or lunacy, including a poem intoned in three languages at once, a Maori song belted out by the young Tzara wearing a monocle as he writhed in epileptic-like spasms and a threatening figure reciting what he called “Fantastic Prayers” while banging a drum and flailing a riding crop.

ACCORDING TO ONE LEGEND, Dada’s name was selected at random from a dictionary. Others recall dada was chosen because it means hobbyhorse in French; or was it taken from a brand of Swiss shampoo? Whatever the origins of the name, the movement’s mix of humor, satire and artistic bravura proved contagious. Its provocative tenets—taking the rebellious aspects of futurism and fauvism to extremes—were proclaimed in a Dadaist manifesto and, after the war, transmitted like a virus around the world by Dadaist artists, most of whom left Zurich, especially the promotion-savvy Tzara. The charismatic Romanian recruited such luminaries as André Breton in Paris, George Grosz in Berlin and Man Ray and Duchamp in New York, a disparate group that cooperated and argued in equal measure.

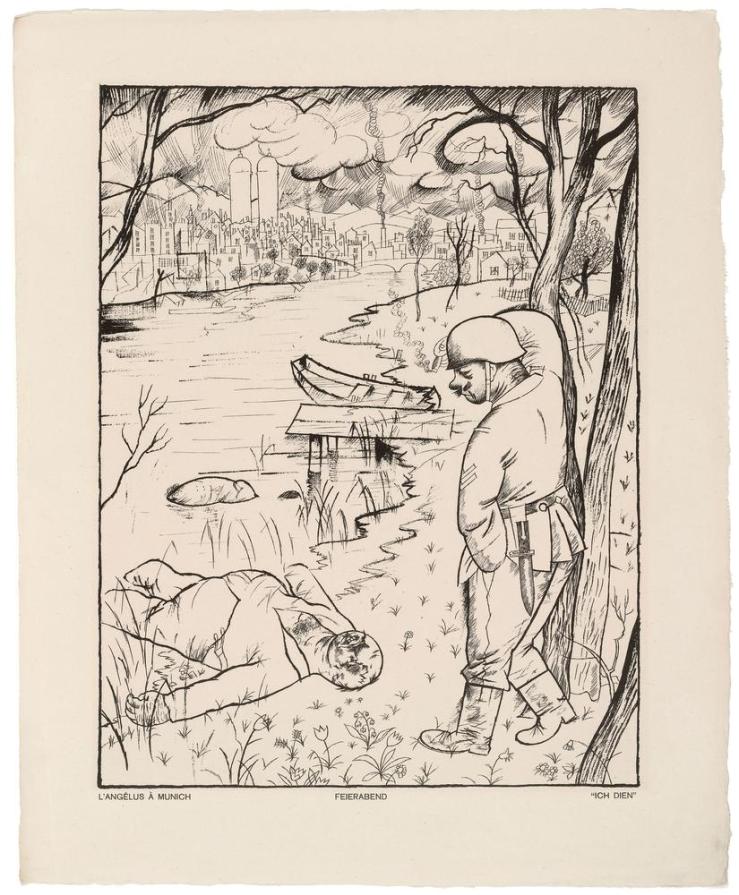

(FEIERABEND) FROM THE PORTFOLIO GOD WITH US (GOTT MIT UNS), 1919, PUBLISHED 1920, PHOTOLITHOGRAPH, COMPOSITION: 15 1/4″ X 11 3/4″. PUBLISHER: MALIK-VERLAG, BERLIN PRINTER: HERMANN BIRKHOLZ, BERLIN, EDITION: 125, ABBY ALDRICH ROCKEFELLER FUND, © THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART/LICENSED BY SCALA/art resource, NY

This month, Zurich is celebrating the “Dada Jubilee” with gusto. On February 5, Cabaret Voltaire will host a Dadaist centennial celebration, to be followed by rituals at dawn for 165 days, each in honor of a different artist. Before traveling to MoMA in New York, Dadaglobe Reconstructed will open in February at the Kunsthaus Zurich, re-creating a volume Tzara planned to publish in 1921 filled with small artworks and writings Dadaists posted to him (Sudhalter spent five years tracking down pieces from public and private collections, each one marked by Tzara with a page reference). In March, Zurich’s Museum Rietberg will stage Dada Afrika, the world’s first exhibition on the Dadaists’ fascination with non-European art. By June, the Dada frenzy will segue into Manifesta 11, a biannual European art show that has chosen Zurich as host, largely because of the Dada connection. The Kunsthaus will also present a major exhibition on Francis Picabia, the French-born rebel who explored art’s limits in New York.

Cabaret Voltaire was Dada’s home for five months, and the performances there have passed into legend. “Dada events were mystical experiences,” says Notz. “They were ecstatic. The artists confronted the audience. They provoked them. It was a pitched battle.”

By mid-1916, unable to afford the rent, the Dadaists were forced to move to other venues. Cabaret Voltaire was turned into a bingo parlor in the 1920s and a series of pubs in the 1980s, enjoying a strange half-life among Dadaism’s admirers as a shrine. Its fate looked grim by the 1990s, when the structure was abandoned, then bought by an insurance company to convert into luxury apartments. Swiss artists were outraged, and in 2002, squatters occupied the site and staged vaguely Dadaist events, such as throwing 2,000 francs from a window to attract supporters. The Swatch company offered to fund its operation as a cultural center if the city council would pay the rent—315,000 francs a year—allowing Cabaret Voltaire to reopen in 2004 and become a fixture on the lively Zurich art scene. Recent visitors include Marilyn Manson and the satirical performance artists Reverend Billy and the Yes Men, who were inspired to dress up as human mops and “clean” a local bank by rubbing themselves on the walls and floor. “They were a bit disappointed nobody called the Zurich police,” says Notz.

Notz hopes the Jubilee will ruffle a few Swiss feathers. “Dada remains a contentious topic in Zurich,” he says. “The city is run by a right-wing party, which equates Dadaism with anarchism and terrorism. The 1916 artists were mostly foreigners and thus immigrants. It’s a red flag for conservative Swiss politicians these days.” But Dada’s future, says Notz, will remain bright as long as there are power structures to rebel against. “Hugo Ball wrote about the ‘economic fatalism’ of the world order, where life is confined and shackled by money, and everything has to be useful and serviceable,” Notz says. “Dadaism tells us that life doesn’t have to be like that. Art is a force strong enough to allow us to break free and to escape our prefigured destiny.”

source: http://www.wsj.com/articles/dada-100-years-later-1453223133