In August 1966, a part-time tutor at St Martin’s School of Art withdrew a book from the college library. His name was John Latham and the book in question was Art and Culture, an essay collection by the doyen of modernism, Clement Greenberg. But Latham didn’t read the book. Instead, he invited friends, students and fellow artists to his house for what he called a “Still and Chew” event. Participants were asked to select a page, chew it to a pulp, and then spit the resultant “distillation” into a flask. Latham added acid, sodium bicarbonate and yeast (“an Alien Culture”), and left the fertile brew to bubble gently.

There it remained until the following May, when the library requested the book’s return, because, as Latham put it, a student of painting was “in urgent need of Art and Culture”. What he delivered instead was a small, stoppered phial, neatly labelled “Art and Culture/Clement Greenberg/Distillation 1966”.

The library was not amused. Latham was informed that his temporary contract would not be renewed. The vice-principal suggested that he smooth things over by apologising for his “bad joke”, but Latham cheerfully refused, observing that he considered such “eventstructures” a crucial part of his teaching practice, and more useful to his students than mere theory.

Latham’s distillation was one of the first acts of British conceptual art, and it serves to encapsulate its early mood, the way it turned deconstruction, even destructiveness, into a creative force. But what was Latham actually doing? Was he being prankish, playfully pricking establishment balloons, or was he making a serious point? What does “eventstructures” even mean? Why Clement Greenberg, and why St Martin’s?

The British conceptual movement of the 60s and 70s changed the face of modern art so fundamentally that it’s hard to reimagine the conditions that precipitated its appearance. Conceptual art was rebellious to its core, a banger in the face of what it saw as stuffy, elitist modernism. This is why Greenberg was a target, though it might also be observed that he had recently described Latham’s book reliefs as “patly cubist”.

What the early conceptual artists wanted to do was expand the definition of art, to blow the bloody doors off the venerable white cube of the gallery. Impure and fluid, worldly and engaged, in many ways conceptual art was a philosophical quest: a search for a vanishing point, for the outer limits of what might constitute a work of art.

In the old days, art had meant things; objects to which the viewer pays solemn homage. But what if art could also be ideas, expressed by way of acts that happened, events in time that left minimal traces in the world? Maybe a person could be a work of art, or a bag of rubbish could. Maybe you didn’t need a gallery at all. Maybe art could take place in the street, or in a field. Maybe it only came into being with the viewer’s presence, and didn’t require witnesses at all.

Conceptual art didn’t come from nowhere. It had an ancestor in the phlegmatic form of the surrealist Marcel Duchamp, whose readymades radically shattered conventional notions of art as a result of skill. But it was also a product of philosophy, the restless questioning of Wittgenstein brought to bear on the arena of the visual.

It sprang up spontaneously in the febrile atmosphere of the 60s, sending up tendrils in London and Coventry, in New York, Berlin, Milan and Rome. In America, minimalists like Ad Reinhardt and Donald Judd were exploding traditional categories of painting and sculpture. In Italy, artists associated with Arte Povera were experimenting with materials, rejecting bronze and oil in favour of dirt and ash.

An interest in ordinary and unclassifiable things also engaged the British contingent, who brought to conceptual art an anti-establishment edge and a deprecating wit. It was never a unified movement, but instead took place in pockets and seams across the country, from the Art and Language movement in Coventry to the defiant experimentation that came out of St Martin’s in the late 60s.

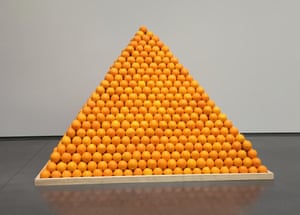

The work the British artists made was at once intellectual and playful, risking charges of pretentiousness in order to challenge received notions of value and meaning. In 1967’s Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), Roelof Louw stacked 5,800 oranges in a pyramid in the London Arts Lab, a hotbed for countercultural hijinks. Over a fortnight, the work gradually shrank as visitors were encouraged to consume the fruit. As Louw put it: “By taking an orange each person changes the molecular form of the stack of oranges, and participates in ‘consuming’ its presence. (The full implications of this action are left to the imagination.)” What he’d done was pass control from artist to viewer; a radical step.

As for the immaculately besuited duo of Gilbert and George, they decided to destroy the gulf between artist and creation altogether, by converting themselves into a lifelong, evolving work of art. In A Message from The Sculptors they declared themselves living sculpture, who could perform in a variety of ways, including “interview sculpture, dancing sculpture, meal sculpture, walking sculpture”. Like Midas, everything they touched was transmogrified, including samples of their hair, their shirts and their breakfast. As they put it firmly: “Nothing can touch us or take us out of ourselves.”

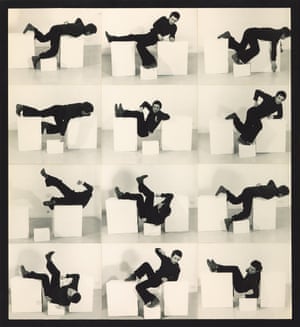

This interest in dissolving or dismantling barriers was a common impulse. For the then British-based Braco Dimitrijević, it meant hanging huge photographs and banners of random passersby in museums, while for Bruce McLean it involved rejecting the gallery in favour of the street, satirising the pretensions of the art world by displaying rubbish on plinths, and using his own body to mock the poses of serious sculpture.

When he was given a retrospective at the Tate in 1972, at the youthful age of 27, McLean held a one-day show, King for a Day, notable for not including any work whatsoever. Instead, he exhibited a neat grid of 1,000 exhibition catalogues, typed in one sitting and comprising a satirical list of 1,000 ideas for imaginary artworks, among them: “403 Earthworks piece, mixed media” and “978 Henry Moore revisited for the 10th time piece”.

Not everyone was so gentle in their approach. One of Latham’s more disturbing works were his Skoob Towers, in which he assembled vast piles of dictionaries, encyclopaedias and textbooks in the streets of London, before setting them alight. They were designed to challenge received ideas about what the sculptural object meant, but they were also disquieting occurrences, with unpleasant historical echoes. Their malevolent energy clearly unsettled the writer AS Byatt. Smoke from burning Skoob Towers drifts through her 1996 novel Babel Tower, conveying the destructive energy of the 60s.

At the decade’s turn, the mood began to change. Conceptual art became increasingly political, and far less easily co-opted by galleries and institutions. This was the era of the Women’s Liberation Workshop and the Artists’ Union; the age of social engagement and collective action, a period in which the Royal College of Art organised a conference for artists, activists and trade unionists, asking among other burning questions whether the artist could ever be a member of the proletariat.

If the language was sometimes humourless or rotely Marxist, the effort to make art matter in the world could produce incandescent results. It was in the 70s that women began to engage more powerfully with conceptual art, wrestling it from the hands of art school boys and using it as a force to convey urgent concerns. As Susan Hiller remarked, “You have no subject matter other than what’s already in language – and what was already in language, for my generation of women, was not what we wanted to say. We wanted to say other things, not necessarily feminist political things, but other kinds of things, and you couldn’t do that without inventing other ways of going about the whole procedure of making art.”

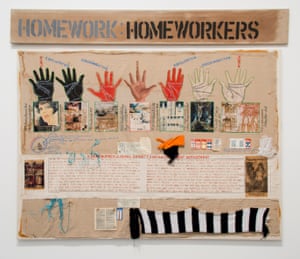

One of the most striking of these works is Mary Kelly’s monumental Post-Partum Document 1973-9, a six-part series in which she formally investigated the mother-child dyad by way of her own relationship with her infant son. Inflected by feminism and psychoanalysis, the work caused tabloid outrage when it was first exhibited at the ICA, because it included stained nappies (you couldn’t have Tracey Emin without Mary Kelly). At once tender and intellectually provocative, a sustained investigation into caregiving and women’s labour, it is among the most significant political artworks of the decade.

As a movement, conceptual art was peculiarly preoccupied with nonexistence, haunted by disappearances and vanishing acts of all kinds. This is particularly true of the artist and photographer Keith Arnatt, one of the greatest British conceptual artists. Arnatt’s wry, witty, curious art was deeply invested in retraction and omission. He liked to make works that left no trace of themselves, burying boxes in the earth and filling pits with turf and mirrors, so that they were wholly invisible until revealed by the passage of his own shadow.

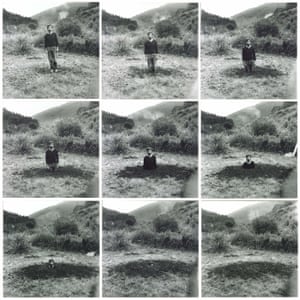

One of his most memorable pieces is Self-Burial (Television Interference Project), which exists as a grid of nine sequential photographs made in 1969. They show a bearded man in jeans standing on a hillside, being slowly swallowed by the earth. In the third photograph, he is buried to his knees; in the eighth, to his eyes. In the ninth, he has disappeared altogether, replaced by a circle of freshly turned soil.

Arnatt was unusual in that he regarded the photographic evidence of his strange acts as crucial, the point itself rather than a necessary but tedious byproduct. By the 70s, he’d moved away from conceptual art altogether, turning his attention to pure photography (he possessed an extraordinary facility for finding art historical echoes in the most unprepossessing of circumstances, including photographs of rotting rubbish that look like Turner sunsets).

For others, the event structure was what counted. Take the land artists Hamish Fulton and Richard Long, who turned walking into an art form, travelling across the country and engaging in subtle, often undocumented interventions with the landscape. The excursions were the real act, though both brought small, humble items back to the gallery: diary entries, stones – compressed aide-memoires of their voyages.

Conceptual art is often misunderstood as trying to claim a sack of rubbish has the same status as a Vermeer. There’s no doubt that it spawned all manner of vacuity, and yet much of the early work retains its questing power, its unsettling occupation of the boundary between object and idea. At its best, it is improbably generous and inclusive, resistant to the capitalist wiles of the art world. An art of vanishing, an art that exists nowhere save in the afterlife of the mind. Want to participate? Then think of Richard Long, setting off from Waterloo in 1967, on a blazing June day. He travelled southwest by train until he reached open countryside, and then he got off at a random station and walked until he found a field. There he paced back and forth in a straight line until the grass was worn flat beneath his feet.

The black and white photograph he took that afternoon is beautiful in its own right: a transient shining line. But that is simply a document. The work of art itself was made out of nothing more than effort and intent, and it returned to nothing, vanishing within hours of its creation. It isn’t possessable. You can’t buy it; it doesn’t exist. All the same, it’s free if you want it. You simply have to conceive of it, to let the idea occupy your imagination.

• Conceptual Art in Britain, 1964-1979, is at Tate Britain, London SW1, 12 April – 29 August. Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone is published by Canongate.